I read Callum Brown’s The Death of Christian Britain this week. Honestly, I wasn’t expecting anything particularly interesting – I was reading it for study, not for fun. You know the story: the Enlightenment, Darwin, the world wars, the end of Empire, the 1960s. After all that British Christianity dies a death of many cuts.

I read Callum Brown’s The Death of Christian Britain this week. Honestly, I wasn’t expecting anything particularly interesting – I was reading it for study, not for fun. You know the story: the Enlightenment, Darwin, the world wars, the end of Empire, the 1960s. After all that British Christianity dies a death of many cuts.

He got my attention when he argued that this story, the one I expected, is pretty much an invention of the 1950s and 1960s and that Britain actually went secular around the very same time as these stories were being spun.

How British Christianity got to the state it is in the year 2000 is currently understood almost universally in terms of the theory of long-term secularisation which was developed academically initially by sociologists, but since the 1950s has been adopted in whole or in part almost universally by historians. The theory of secularisation posits that relgion is naturally ‘at home’ in pre-industrial and rural environments and that it declines in industrial and urban environments. The rise of modernity from the eighteenth century… destroyed both the community foundations of the church and the psychological foundations of a universal religious world-view. Secularisation, it is traditionally argued, was the handmaiden of modernisation, pluralisation, urbanisation and Enlightenment rationality… For most investigative scholars of social history and sociology, British industrial society was already ‘secular’ before it had hardly begun.

In the 1950s and 1960s…British people re-imagined themselves in ways no longer Christian – a ‘moral turn’ which abruptly undermined vritually all of the protocols of moral identity. Ironcially , it was at this very moment that social science reached the height of its influence in church affairs and in academe. Secularisation theory became the universally accepted way of understanding the decline of religion as something of the past – of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The 1960s viewed itself as the end of secularisation. But by listening to the people themselves, this book suggests that it was actually the beginning.

Brown reaches this conclusion because his approach is different to the social scientists’. Instead of counting things – bums on seats, Sunday School enrolments, confirmations, ordinations (he claims this is a shallow Enlightenment way of understanding religion) – he looks to what people were saying and thinking, how people framed themselves and their society in Christian terms. He finds that Britain was Christian until the 1960s

What changed?

This was the other surprise. He says women.

Women were the bulwark to popular support for organised Christianity between 1800 and 1960s, and it was they who broke their relationship to Christian piety in the 1960s and thereby caused secularisation.

Brown takes us back to the nineteenth century and traces discourses of evangelical femininity and piety.

One of the great mythic transformations of the early nineteenth century was the feminisation of angels. Until the 1790s, British art and prose portrayed the angel as masculine, or at most, bisexual – characteristically muscular, strong and even displaying male genitalia, and a free divine spirit inhabiting the chasms of sky and space. But by the early Victorian period, angels were virtuously feminine in form and increasingly shown in domestic confinement, were no longer free to fly. Women had become divine, but an angel now confined to the house.

17th Century Angels

19th Century Angels

In the Middle ages and early moden period, the way for women to model Christian virtue was to act ‘masculine’. ‘Icons of female piety, such as martyrs and ascetics, had been represented as ‘masculine,’ while femininity, menstruation and childbirth were regarded as dangerous and polluting to piety’. Women were considered prone to superstition. From the 1500s, he explains, ‘a wife’s feminity was a threat to piety and household, and a husband established his moral status by controlling her’.

But around 1800, as the re-imagining of angels reflects, religion became a feminine attribute and masculinity the antithesis of religiosity. Women, now, were to control the immoral ‘masculine’ tendencies of men. Women were the cornerstone of the evangelical scheme for moral revolution – their moral and domestic qualities would sanctify the home and thus the nation as a whole. He does, of course, address ‘muscular Christianity’ as an ‘attempt to redefine manhood’, concluding that it never managed to change the dominant negative discourse on male religiosity.

Whereas in the nineteenth century, pious women were believed to have a positive moral and converting influence on men through providing a happy home, by the twentieth the happy home became the ends in itself.

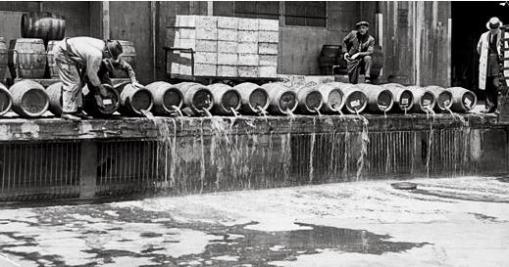

The artefacts of male temptation – drink, betting and pre-marital sex – were no longer the problem: it was the discontented rather than immoral manhood which the woman had to combat in the home, and to do this she had to make the home an unremittingly happy place…

Women were no longer being required by discourse to challenge men into submission to a pious domesticity, but to provide a contented domesticity for them.

Femininity, your identity as a woman, was so tied to Christianity and morality that, though men had been gradually leaving churches and Christianity for a while, this was not really an option for women.

From early in the twentieth century, there is plenty of evidence…of men disavowing churchgoing, and even rejecting Christianity. But for women, this type of personal journey away from religion was extremely difficult and comparatively rare before the 1950s. It was difficulty because a woman could not just ‘drop’ religion as a man could; her respectability as a woman, wife and mother, wether she liked it or not, was founded on religion whether she went to church or not.

Women were pious and piety was feminine. British Christianity itself rested on a domestic ‘Christian’ womanhood.

the 1960s

You can see where this is going. Everything changed in the 1960s.

The 1960s was a key decade in ending ‘the Enlightenment project’ and modernity. In its place, the era of postmodernity started to mature. Structural ‘realities’ of social class eroded, and there was a repudiation of self-evident ‘truths’ (concerning the role of women, the veracity of Christianity, the structure of social and moral authority)…

Just as environmentalism and the anti-nuclear movement started to challenge science in the sixties, so post-structuralism and feminism would come within a decade or so to challenge social science.

But the immediate victim was Christianity, challenged most influentially by second-wave feminism and the recrafting of femininity.

We know what happened. Women find new ways of being women – strong and invincible. Women started finding their identity in work, rather than home. They secularised their identity. Women pointed out the double standards, the freedom men enjoyed and the restrictions they endured. Women stopped going to church. They had had enough.

The keys to understanding secularisation in Britain are the simultaneous de-pietisation of femininity and the de-feminisation of piety from the 1960s.

Before 1800, Christian peity had been a ‘he’. From 1800 to 1960, it had been a ‘she’. After 1960 it became nothing in gendered terms. More than this, the eradication of gendered piety signalled the decentring of Christianity – its authority and its cultural significance.

Brown isn’t sure if this is what happened in Australia and New Zealand, but it seems likely. North America was a bit different, he argues. Over there, the discursive challenged has emerged but not triumphed – there is still a conflict underway.

concluding thoughts

I have never quite understood the evangelical reaction to second wave feminism, the complete disdain for a movement which, as I understand it, was mostly a good thing. Of all things to hate, why feminism? Why not consumerism or materialism or something else? Equal pay, equal rights, equal respect, equal opportunities and equal moral standards – justice – all seem perfectly compatible with Christian belief to me (I would even say they originate in Christianity). But, if feminism was the blow which took out Christian Britain (and Christian Australia?), then I understand the gut reaction to all things feminist and the zeal of the current complimentarian movement.

A better response to this experience, I believe, is not to try and turn back the tide and restore femininities and masculinities to what we imagine they once were (whether you find ‘Biblical’ gender roles in the 1950s, 1800s or 1730s). As we have seen, pinning certain virtues onto one gender or another is a dangerous path: it ends up excluding some and burdening others. Righteousness is neither masculine nor feminine, it’s for all Christians, women and men (as is submission, gentleness, patience etc. etc.).

Instead, we need to think about what might be other ideas and identities we have put our faith in and called ‘Christianity.’ The reconstruction of femininity in the 1960s, I believe, was a good thing. The problem was that Christians had allowed their faith to be so attached to a culture of moral, domestic, idolatrous femininity that when this was challenged and abandoned, Christianity no longer made sense. What beliefs or identities other than ‘follower of Jesus’ are we relying upon today that, were they to be challenged or swept away, would risk bringing Christianity down with them?

What do you think of Brown’s analysis? I’d love to hear what people who were actually there for the 60s think. What other identities or ideas do we risk pinning our faith on now?

I’ve been reading Andrew Walls’ The Missionary Movement in Christian History. Not a flashy title, but a fascinating book. It was published almost 20 years ago, so I’m a little slow on the uptake – perhaps everyone else has already been here, done that – but his writing about the incarnation as God’s translation of the Word for us, and the on-going re-translation of the gospel is just beautiful. If, like me, you’re also 20 years behind the times on missiology, it’s worth reading.

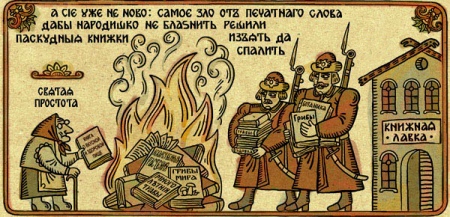

I’ve been reading Andrew Walls’ The Missionary Movement in Christian History. Not a flashy title, but a fascinating book. It was published almost 20 years ago, so I’m a little slow on the uptake – perhaps everyone else has already been here, done that – but his writing about the incarnation as God’s translation of the Word for us, and the on-going re-translation of the gospel is just beautiful. If, like me, you’re also 20 years behind the times on missiology, it’s worth reading. But what’s going to happen as we increasingly move towards an audio-visual culture? We already receive most of our information this way, how much longer do we expect books to hold on? Can evangelicalism adapt for an audio-visual culture? Perhaps – and maybe the answer is along the lines of those slick TGC monochrome clips with the Great Men in earnest discussion. Or perhaps evangelicalism will evolve, re-contextualise, translate itself into something else altogether. What do you think? Is evangelicalism prepared for the future?

But what’s going to happen as we increasingly move towards an audio-visual culture? We already receive most of our information this way, how much longer do we expect books to hold on? Can evangelicalism adapt for an audio-visual culture? Perhaps – and maybe the answer is along the lines of those slick TGC monochrome clips with the Great Men in earnest discussion. Or perhaps evangelicalism will evolve, re-contextualise, translate itself into something else altogether. What do you think? Is evangelicalism prepared for the future? I read Callum Brown’s The Death of Christian Britain this week. Honestly, I wasn’t expecting anything particularly interesting – I was reading it for study, not for fun. You know the story: the Enlightenment, Darwin, the world wars, the end of Empire, the 1960s. After all that British Christianity dies a death of many cuts.

I read Callum Brown’s The Death of Christian Britain this week. Honestly, I wasn’t expecting anything particularly interesting – I was reading it for study, not for fun. You know the story: the Enlightenment, Darwin, the world wars, the end of Empire, the 1960s. After all that British Christianity dies a death of many cuts.

Finally, I will just mention that Peter Enns is one evangelical who is willing to talk about this stuff with a popular audience. I don’t agree with everything he writes, but at least he’s opening a conversation. He is author of

Finally, I will just mention that Peter Enns is one evangelical who is willing to talk about this stuff with a popular audience. I don’t agree with everything he writes, but at least he’s opening a conversation. He is author of